:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(jpeg)/Health-GettyImages-2161043687-3bb728b542574bd28c55b658226ea823.jpg)

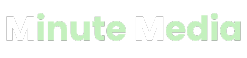

The Biden Administration proposed a rule on Tuesday that would require Medicare and Medicaid to cover weight loss drugs as treatments for obesity. If enacted, the policy would go into effect in 2026.

Currently, these programs cover popular glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) drugs such as Ozempic, but only for indications other than weight loss, such as diabetes or heart issues. But if the rule were to go into effect, people could access these medications through their insurance to help them lose weight, even if they didn’t have another condition.

Over 40% of Americans have obesity, and the proposed rule could open up access to weight loss drugs for over 7 million people.

Public support for and interest in these new GLP-1 weight loss medications has been building in recent months, said Mariana Socal, MD, associate professor in the Department of Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. About one in eight Americans say they’ve tried a GLP-1 drug.

“These drugs have been receiving [increased] public attention in the second half of 2024,” she told Health.

Though GLP-1 drugs were initially approved for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (Ozempic, Mounjaro, Victoza) and for obesity (Wegovy, Zepbound, Saxenda), they have increasingly been linked to other health benefits—the drugs may be able to lower cardiovascular disease risk and slow the progression of chronic kidney disease, among other benefits.

The fact that these drugs could be helpful outside the context of obesity could be one reason why the Biden Administration is proposing this rule now, Socal said.

However, some are concerned that the expanded coverage would cost Medicare and Medicaid substantially. If half of the people with obesity who are enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid took Wegovy or another weight loss drug, the agencies could spend $166 billion a year, according to a statement from Senator Bernie Sanders, the Chairman of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions.

The proposed rule would also have to be backed by the Trump Administration, and there will likely be other roadblocks as well. “I do [foresee] legal challenges to the validity of this rule,” Socal said.

Here’s how the rule might change current Medicare and Medicaid coverage, who stands to benefit the most if it’s enacted—and what could stall or stop this proposed change.

The proposal, coming from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), would significantly expand coverage of anti-obesity medications.

Though it highlighted the benefits of GLP-1 drugs, the HHS didn’t explicitly mention which name-brand medications might be approved and for whom should the rule be enacted. We also don’t know if—or how much—people enrolled in Medicare or Medicaid would have to pay out of pocket.

However, the White House billed the proposal as another prescription drug cost-cutting measure, saying that the coverage could lower out-of-pocket costs “by as much as 95 percent for some enrollees.”

“This proposal would allow Americans and their doctors to determine the best path forward so they can lead healthier lives, without worrying about their ability to cover these drugs out-of-pocket, and ultimately reduce healthcare costs to our nation,” the Biden Administration said in a statement.

Medicaid programs in a handful of states cover GLP-1s for obesity, but the rule would likely give millions more people access to the drugs—specifically, the new rule could benefit about four million Medicaid enrollees and 3.4 million Medicare enrollees.

The effects could be significant, especially considering how obesity puts people at a higher risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and some cancers.

“It is only logical that this might happen over time because there are so many complications that can come from untreated weight gain,” Socal said. “If it weren’t for the high price of these drugs, we would already be seeing [this as] an option.”

Making weight loss drugs more accessible could also be helpful in addressing the growing health disparities in the U.S.

Given that anti-obesity medications can cost upwards of $1,000 a month out of pocket, lower-income individuals could have trouble accessing new GLP-1 drugs. Previous research has shown that use of some anti-obesity drugs is greater among people with higher median incomes.

Additionally, people of color are at an increased risk of obesity, but historically, higher percentages of white Americans have taken some anti-obesity medications as compared to Black, Hispanic, and Asian Americans.

Right now, experts don’t know how the incoming administration will handle the proposed rule; it’s possible that Trump’s cabinet may not favor the changes to Medicare and Medicaid.

Questions still remain as to whether the rule change would create further budgetary problems for Medicare and Medicaid or if making the medication easier to access might actually bring down the amount of money the U.S. healthcare system spends on obesity: Currently, that sits at around $173 billion annually.

In addition to cost and budget concerns, there could also be impending legal hurdles, too.

“I think there is a legal element here that we’ll be seeing in the future,” Socal said.

That’s because, right now, Medicare and Medicaid cannot legally cover medications for a number of health conditions, including weight loss or weight gain. That legislation may need to be changed in order for more people to have coverage of these medications through Medicare and Medicaid, Socal said.

“Future challenges for this proposed rule are not going to be around the clinical dimensions, but the legislation in place that prohibits coverage of weight loss drugs under Medicare and Medicaid,” she explained.

It’s too soon to say what kinds of ripple effects the rule, if enacted, would have in terms of Americans’ health. However, the proposal itself represents a healthy shift in the way we view obesity in the U.S., Socal said.

“The rule reflects a very important change in the understanding of obesity,” she said. “[We as a society would be] understanding it more [in terms of] medical care and not so much dependent on behavioral care.”